100 Days

I always wanted to ride 100 days in a single season. I vividly recall the goal taking root in my mind. This ambition developed after reading about Jake Burton Carpenter's commitment to it in the 2000s. An unforgettable header image from his blog post captured my attention: “100” peed into the snow atop a mountain peak, against an expansive winter vista.

In an article that is probably long lost to the internet, Jake wrote about what first inspired him to create his goal, and how he set about accomplishing it. Day one was usually in Chile or New Zealand during North America’s summer; from there, he chased winter around the globe. For him, it represented staying connected to the soul of snowboarding and ultimately his customers. For me, it represents the culmination of my life's commitment to snowboarding. Still though, I haven’t hit it yet.

Although my goal is the same as Jake’s, it isn’t really. I don’t have millions of dollars and global travel on a whim at my disposal. For Jake, the challenge was primarily physical. For me, it’s more logistical. Accomplishing my goal requires being on the mountain nearly every day during the short season afforded to me. In my twenties, I took jobs that kept me on snow. First as a snowboard instructor and then as a park manager. During my time as a park manager, I came close. On pace to hit 100 days by the end of March, I tore my ACL on Valentine’s Day and was sidelined for several weeks.

My ACL injury, which I’ve written about before, forced an existential crossroads. For the first time, it appeared that 'more snowboarding' was not the answer. More snowboarding, at the expense of everything else, caused the muscle imbalances and adrenaline-seeking behaviours that led to the injury. It also forced me to recognize I was breakable. The days of throwing myself haphazardly off jumps by day and consuming my weight in beer by night were long behind me.

Riding 100 days in a season is more than just a satisfying round number. It means going out on cold days, low visibility days, days when you have a runny nose, or when you just don’t feel like it. It means trading in dinners with family for night laps. It means that, for half the year, life revolves around snowboarding.

So what’s it all for? Ego? What does riding 100 days in a single season say about me when I’m head down on the chairlift, enduring pouring rain and biting winds just to check a day off? Growing up a grizzled east coaster, I took pride in being out there when others weren’t. But in those moments, it’s difficult to pretend I was out there for the love of the game. Where exactly was the progression?

If I ride 100 days in a season and don’t post about it on social media, did it even happen? Would I feel a sense of accomplishment from finally catching my white whale? My instinct is no. I’m running away from the inevitable. One day the winter will end and I will be back on my own, without snowboarding. To the young, the years are like dollars to billionaires. There’s no need to mourn the season's end; there will always be another winter. Except there won’t.

The mortality rate for humans is 100%. Many systems, ranging from religion to capitalism, help us run away from this uncomfortable fact. But as our years accumulate and time seems to accelerate, the run must become a sprint to maintain our ignorance. Even the longest lived lives are deceptively short. Living to 80 years old equates to only about four thousand weeks on this earth. If I'm lucky enough to live into my 90s like my grandparents, that would amount to about 4700 weeks.

The human condition plays a cruel trick. We are blessed with the capacity to plan for the future, yet we have almost no time to execute these plans.

1300 Days: Embracing Finitude

Four Thousand Weeks can be an uncomfortably small number to own up to, especially considering I’m nearing the halfway point. Time seems to be accelerating too. I could add or subtract a couple hundred weeks depending on how I curb certain habits, but ultimately, no one makes it out alive. I became a father at a young age, so were it not for my daughter being in high school and my receding hairline, I could almost swear I was still in my early twenties. I blinked, and two decades passed. As Roger Waters once sang:

“And then one day you find ten years have got behind you. No one told you when to run, you missed the starting gun.”

The point of quantifying my lifespan isn’t to justify reckless actions like throwing myself off dangerous cliffs or buying a sports car. It’s to acknowledge that time is limited. It’s to cultivate a better appreciation for it. Time is our most valuable non-renewable resource. It’s the only thing we can never get back. Because of that, there’s no sense in dwelling on hours, days or weeks wasted in the past. However, there is tremendous value in being more intentional about the way I spend my present and plan for my future. With every choice I make, I actively omit the infinite possibilities of other things I could be doing with that time. Economists call it opportunity cost.

As Oliver Burkeman states in his book, which inspired this article:

“... what’s required is the will to resist the urge to consume more and more experiences, since that strategy can only lead to the feeling of having even more experiences left to consume. Once you truly understand that you’re guaranteed to miss out on almost every experience the world has to offer, the fact that there are so many you still haven’t experienced stops feeling like a problem. Instead you get to focus on fully enjoying the tiny slice of experiences you actually do have time for - and the freer you are to choose, in each moment, what counts most.”

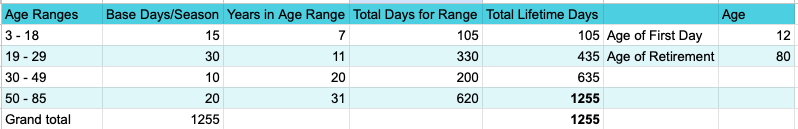

Most snowboarders will never experience a 100-day season. There are an exceptional few that regularly meet or exceed that number, but most snowboarders ride between 10 and 30 times per year. Taking the same back-of-the-napkin approach as the Four Thousand Weeks concept, I got curious how many days one might expect to be able to snowboard in their lifetime. So, as is my tendency, I made a spreadsheet. The short answer is about 1300 days, but I am aiming for around 1800.

My calculations take a few assumptions into account. First, this is based on an ambitious rider. From ages 3 to 18, with limited access to transportation to the mountain and school preoccupations, I’m assuming a 15-day season is average for that age range. As high school finishes and one is more likely to have access to a car and more free time to spend riding, I’m assuming an ambitious rider will make it out 30 days per season from ages 19 to 29. From 30 to 49 life’s responsibilities begin to bear down, and it can become more difficult to get out as often as one once did. For this stage I’m assuming about 10 days per season. From 50 to 85, with the freedom of an empty nest and eventual retirement, I’m assuming about 20 days per season.

I've also assumed that the individual in the example starts snowboarding at age 12 and retires at 80. This, of course, is all customizable in my spreadsheet. The calculation is imperfect. It doesn't account for seasonal variance, injuries, beach vacations, or many other realities of life. If you think you can improve it, feel free to make a copy and do your own calculations. It isn’t supposed to be a perfect calculation though. Neither is Four Thousand Weeks. It’s supposed to germinate a state of mind.

For reference, assuming a season lasting from November 24th to April 15th, a weekend warrior can expect to ride about 42 days, going both days every weekend. Add in a few long weekends and a snowboard vacation and it’s possible for the extremely dedicated rider with a civilian job to hit the 50 day mark in a single season. However, this comes at the cost of almost all other free time. Most snowboarders earn their income outside the industry, and even fewer have had the foresight to start the world's largest snowboard company. To them, 100 days remains a distant dream, one that I would argue isn’t worth pursuing.

If every day spent snowboarding is a day spent not doing something else, the pursuit takes on the sheen of an escapist fantasy. One could argue the pursuit of this arbitrary ‘100 days’ goal prevents us from participating in many of life’s other important areas of progression. Many of these areas can end up supporting the longevity of our riding. If I’m on the chairlift in the pouring rain on a Tuesday afternoon, merely checking a box, it means I'm not using that time to position myself physically or financially to ride into my 70s.

To embrace Four Thousand Weeks is to engage in meaningful and enriching activities. With this in mind, I believe there are better ways to spend my time than being strapped to a board in a rainstorm. Depositing a potential snowboarding day into the 'bank' and opting to focus on other adult responsibilities instead can, counterintuitively, afford more snowboarding days later in life. Turns out, compound interest pays off.

Snowboarding has always felt like an escape from the oppressive forces of Father Time, but it’s all a trick. Within our personal snow globe, time becomes elusive. It stretches out short moments of airtime or unfettered descent, all the while compressing immersive days and entire seasons into a retrospective blink of an eye. Outside our personal snow globe, the world turns on. We return from the mountain, oblivious to the toil and expansive days our fellow humans endured, a day older just the same.

The Snowboarders Lifecycle

Don’t get me wrong. I still intend to achieve the 100-day goal. I’m a man of many contradictions. But as with other things, I’m more patient now. To achieve 100 days, I can no longer omit things from my life for the sake of snowboarding. Instead, inclusion becomes the key. By including time for strength and cardio fitness, I’m adding days to the bank. By including loved ones on my rides, snowboarding takes on a meaning beyond my individual skill. Devoting time to professional development opens doors to greater financial freedom, enabling longer, more enriching snowboarding vacations, and perhaps one day, a ski-in/ski-out property. These all add days to the bank.

The saying “the worst day snowboarding is better than the best day at the office” is just simply not true. The best days at the office fuel season passes, new equipment, and snowboard vacations. The worst days snowboarding come with broken bones, avalanches, and lost friends. Embracing the finitude of life and snowboarding thus demands calibrated judgment on the best use of each day: on the snow or in the bank?

The days I spend on snow should be unhindered. In snowboarding as in life, I want to be the one to choose when I stop. I want to call ‘last run’ when I feel fulfilled, not because my body is fatigued or due to an injury that leaves me strapped into a ski patrol toboggan. In order to ever flirt with the 100 number again, I’ll need to develop a systems-based approach. I will have to maintain a consistent workout routine, even during the off season. I’ll need to live somewhere with access to summer snowboarding. I’ll need to surround myself with like minded people who push me to be better every day. In other words, I’ll need to be living the dream – a pursuit that resonates deeply with the desire to embrace each moment, both on and off the snow. Walking this path is another step towards balance, growth, and making the most of my thirteen hundred days, and hopefully more.

This is a far cry from sleeping in my car at the base of the resort, using the hand dryers in the bathroom to unfreeze my snowboard boots in the morning. It beats loading onto the chairlift in pouring rain during a January thaw. It’s far more enjoyable than slamming my ribs against a cold metal rail, a miscalculation caused by fatigue, and unquestionably better than subsisting on ramen noodles and peanut butter sandwiches just to afford gas to get up to the mountain. All this was in pursuit of 100 days as well. A few years ago, I would have classified the previous few sentences as living the dream. Now it seems like desperation.

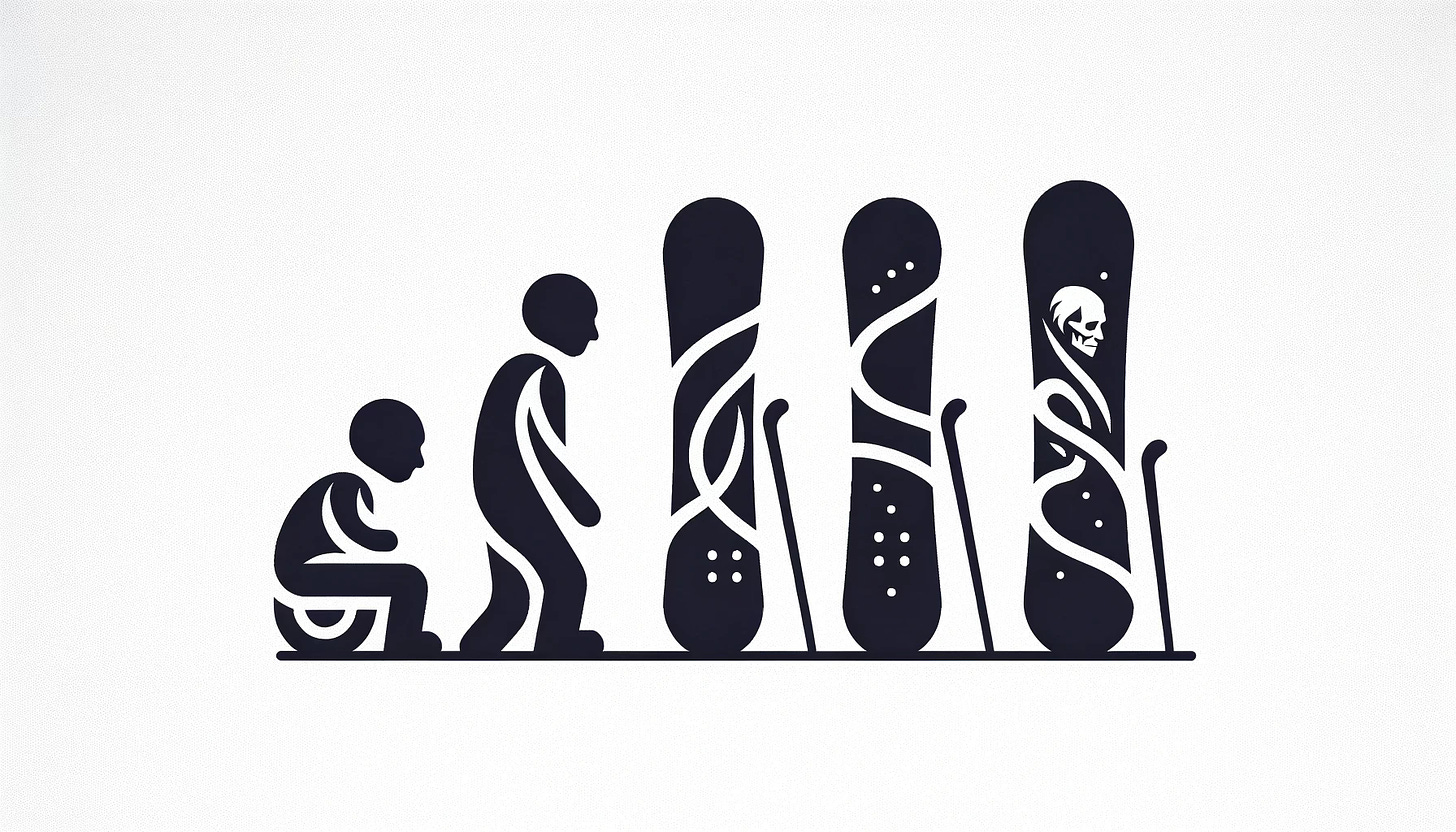

That’s fine. I hope to reproduce my own interpretation of the classic professional snowboarder's lifecycle during my time on this earth. For most big-name professional snowboarders, whether Travis Rice, Craig Kelly, Jake Blauvelt, or Jeremy Jones, proving themselves on the competition circuit was the necessary evil that afforded them access to truly transcendent experiences. Each of these pros excelled in the race or slopestyle circuits before shifting to produce video parts. Over time, those video parts tended to include less time on the resort or in the streets, and more time in the backcountry. Eventually, whether there were cameras rolling or not, they rode off into the sunset to enjoy their remaining years in the freedom of the backcountry.

In my teens and twenties, my ego was tied to park riding, jumps, and rails, but I believe that phase has been sufficiently fulfilled. Competing in the X Games was never my ambition. Instead, my autotelic nature now gravitates towards simpler yet deeply rewarding pursuits like honing my switch riding and mastering the carve. These activities, well-suited for longevity, not only offer experiences as rich and immersive as park riding but also promise a sustainable path to enjoy snowboarding well into my 70s. As I continue to evolve in areas beyond snowboarding, I'm setting myself up for many more years snowboarding, ensuring each is filled with a sense of security and leaves ample space for appreciation.

Until then, I'm committed to seizing every opportunity, filling as many days as possible with powder slashes with friends and exploring new terrain. I’ll gladly stretch these fleeting moments out and then compress them in a blink. At the same time, I'll continue to focus on growing beyond snowboarding that will lay the groundwork for future opportunities to ride. Yet, when the snow's whisper beckons irresistibly, I'll still joyfully cast aside my adult responsibilities and surrender to the mountain's call — because, after all, we only live once.